#ศาสตร์เกษตรดินปุ๋ย : ขอบคุณแหล่งข้อมูล : หนังสือพิมพ์ The Nation.

POTOMAC, Md. – I broke the rules at Glenstone, the contemporary art museum in Potomac, only moments after passing the pale-gray wooden walls of the entry pavilion.

The staff who greeted me a few minutes earlier had laid out the dos and don’ts of how we were to behave upon entering the grounds of one of the first major art museums in the region to begin a partial reopening. Always wear a mask. Keep social distance. Stay on paths. No touching allowed.

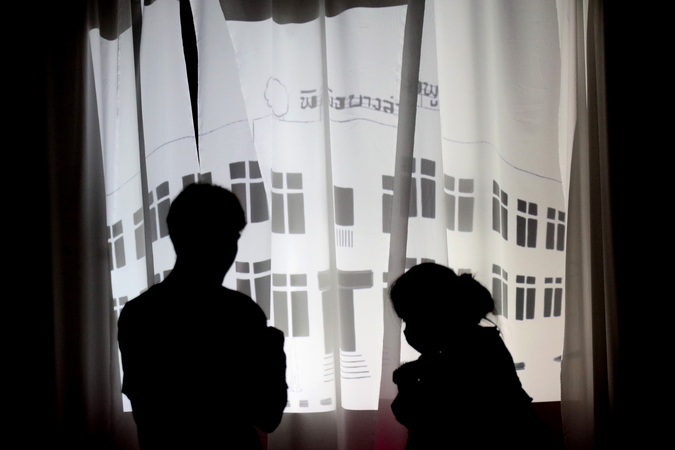

Arrival Hall at Glenstone, which opened its gardens and grounds to a limited public audience in Potomac, Md., on June 4. Visitors were asked to pay attention to social distancing rules and wear masks. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post photo by Michael S. Williamson

But, no sooner had I reached the open meadows that are the overture to this carefully curated 300-acre landscape than my right hand brushed against the tall grass bending over the gravel path. Reflexively, I pulled off a few dried seeds and rubbed them between my fingers.

During the coming weeks and months, as museums begin to reopen around the country, there will be a lot of new rules, and a lot of reprogramming our expectations and behavior. Glenstone has been a work in progress since it opened to the public in 2006, as a small gallery on the grounds of the home of museum founders Mitch and Emily Rales. A year and a half ago, the museum took a giant leap to world prominence when it unveiled a 204,000-square-foot building called the Pavilions, designed by Thomas Phifer, to display the Rales’s vast and deep collection of modern and contemporary art. And then the coronavirus hit, and Glenstone, like almost every venue, was off limits.

The facility, which uses an online reservation system, reopened this week as “an outdoor experience.” The museum buildings are still closed, as are the entry pavilion, cafe and restrooms, so the museum is suggesting visitors read its guidelines and be prepared. “They should check the weather before they come, wear sunscreen and bug spray, bring their own water, and carry their trash out with them,” said Emily Grebenstein, communications manager for Glenstone.

The outdoor sculpture collection, however, is mostly accessible, the grounds are lush, and on Thursday morning the scattered couples, friends and family groups that scored one of the 210 daily online reservations were giddy about the experience.

Thais Austin, 59, a real estate agent who was among the first visitors, said that in the old days, before the coronavirus, she had her cellphone programmed to alert her if there was an art exhibition open near any property she was visiting as part of her job. She said she “used to go to everything.”

“I really miss my museums in D.C.,” she said. “It has been heartbreaking to me. I jumped on this within five minutes of getting their email about reopening because I knew that it would be booked out. We need some joy right now.”

Austin was visiting with a friend, Melanie Edwards, 40, who lives in the same condo building in Chinatown. Edwards, a musician, was celebrating having recently received an arts grant from the District of Columbia, which will help her get through what has become a devastating and extended period of unemployment. “This is the third and a half month in and it’s just dire straits, and I don’t know when I’ll go back to the performing world.”

The two women expressed a sentiment echoed by others: disappointment that more of Glenstone wasn’t open, but excitement at having the place mostly to themselves.

Tom May, 70, a retired tutor at St. John’s College in Annapolis, came with his wife, Pam, his son and his son’s fiancee. As the midday temperatures began creeping toward the 90-degree mark, he stood next to a 2001 Richard Serra sculpture, a canted and interlocking spiral of oxidized metal plates called “Sylvester.” This was his third visit to the venue.

“I was really just so delighted by it,” he said, remembering his first encounter with the Serra. He was even more impressed on Thursday. “It’s a different time of day,” he explained, as the sun cast bright, blade-like shadows on the ground between the steel panels.

He mentioned George Floyd, who died while in police custody more than a week ago, and the anger that still seethes in America today. “There is this very strong sense that we are not there yet,” he said, and added that the crisis is raising new expectations, which is a good and necessary thing. “Coming here in the presence of both nature and art recontextualizes what those possibilities might be.”

The Serra sculpture is so large, it beckons you in, to walk the spiraling path between its ominously tall and heavy walls, until you reach the center point, where everything but the sky disappears. It’s a narrow passage, however, and that requires visitors to be conscious of each other’s presence, and safety. It became a one-way street on Thursday, and those who wanted to enter had to listen for voices inside and wait until others exited before heading in.

I carried my grass seeds with me past the Serra, down the path into the woods below, to see my favorite work, Andy Goldsworthy’s 2007 “Clay Houses,” which were closed. On my way back, I again passed the Pavilions where, if you stood on tiptoe, you could see that there were waterflowers in bloom in the aquatic courtyard below. But there was no access to the courtyard, and so no one was sitting on the bench that juts out into the pond, a popular spot that is so detached from the ordinary world, so lost in its own perfect little vision of water and sky, that two’s a crowd.

Behind me, on a perfectly flat swath of ground, was Michael Heizer’s “Compression Line,” an elongated metal box set deep into the earth such that its walls are forced together in the center. When I first passed it on the way in, its “compression” seemed a perfect metaphor for social tension, for the confinement of the past months, for the strained-to-breaking nerves of a society on edge. But now it had lost its metaphorical specificity, and seemed to be what it was when I first encountered it a few years ago: a compelling visual object, suggestive of a multiplicity of things and feelings, but not a dirge crafted for any one moment plucked from the timeline of history.

I dropped my grass seeds somewhere along the way, and didn’t pluck any more. The experience seemed distinct and different from a visit to a museum, and not just because the museum buildings were closed.

Nor did it seem like a visit to a park, or a stroll through nature. There were squirrels in the woodlands, multiple wildflowers in bloom and fallen blossoms from the tulip poplars. But the scattered presence of people in a public landscape was more significant than anything else, people who were extravagantly friendly in their socially distanced greetings, people who clearly took pleasure in each other’s presence, always at least six feet apart. Even the masks they were wearing were festive, and eyes sparkled above them.

Glenstone has, and will always have, the Glenstone problem, which is that it is a fantasy place, created by two extraordinarily rich people, so that others may contemplate a form of human endeavor – contemporary art – that is sometimes blindingly prophetic and revelatory, and very often silly to the point of being an inexcusable waste of resources, financial, cultural and intellectual. Glenstone, like contemporary art, is always perched on the precipice of being ridiculous.

On Thursday, however, it was an oasis where life felt fragile and deliberate, and everyone there was glad to be there.

“I thought that this would be, and it is, therapeutic,” said May. “Not to forget, but to heighten and re-energize what it is that we should be doing and thinking and feeling.”

So art is what it always was, only more so: a privilege, a pleasure and a problem. There’s no indulging it that doesn’t leave you struggling with a paradox: It is not sufficient, in itself, to make the world a better place, yet the world would be far worse without it.

The statue of Jefferson Davis in Richmond was defaced before being toppled to the ground. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post photo by John McDonnell

The statue of Jefferson Davis in Richmond was defaced before being toppled to the ground. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post photo by John McDonnell

.jpg)