It can be unsettling to arrive at Denver International Airport, where a giant wildly bucking royal-blue horse glares at you with glowing red eyes while you drive up to the terminal. The statue, Luis Jiménez’s “Blue Mustang,” makes for an unforgettable vision – exactly what we look for when we travel.

Thankfully, other airport animals adopt a more friendly demeanor. In Sacramento, a giant red rabbit dives into a suitcase, filling the three-story atrium as visitors traverse linked escalators alongside its 56-foot-long body. Artist Lawrence Argent installed “Leap” in 2011.

And in Las Vegas, four outsize denizens called “Desert Wildlife” – a rattlesnake, tortoise, horned lizard and jack rabbit, crafted by David L. Phelps – invite travelers to climb on them. Their surfaces are cracked like hard-baked desert soil, an effect created by glass-fiber-reinforced concrete. Once, a scorpion also prowled the floor of McCarran International’s then-new Gate D terminal, but it was “retired,” says Phelps, 63, who lives in Oklahoma City.

Phelps speaks eloquently about the value of art in everyday spaces. “Airports are so generic,” he says. “If you were blindfolded and dropped into one, you’d have no idea where you were. The art, if it’s good, gives an individuality to the airport.” He adds: “There’s a real select minority of people that are aware of art and go to museums. This exposes more people to it. The media tends to focus on Jeff Koons and people who turn into stars. For the rest of us, art is like a religion, like a pursuit for beauty … which is kind of rare in our society.”

“Blue Mustang,” a 32-foot sculpture by Luis Jiménez, at Denver International Airport. MUST CREDIT: Denver International Airport

“Blue Mustang,” a 32-foot sculpture by Luis Jiménez, at Denver International Airport. MUST CREDIT: Denver International Airport

Not surprisingly, a lot of airport art involves ceiling installations, to fill the vast spaces in terminals without impeding fast-moving travelers. Alice Aycock’s “The Game of Flyers Part Two” in Washington Dulles International Airport suspends aluminum, fiber optics, LED lights and neon high above people’s heads in an attention-grabbing asymmetrical spread reminiscent of flight, perfect for the snaking security line beneath it.

Chicago O’Hare’s “Sky’s the Limit” by Michael Hayden perks up the weary traveler. It consists of a 745-foot tunnel lit by a mile of neon tubes, amplified by enough mirrors to make the sculpture feel much larger, as passengers use moving walkways through its eerie bowels.

Similarly, in Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, a 450-foot ceiling installation called “Flight Paths” casts a murky, rave-like atmosphere over an otherwise utilitarian hallway of moving sidewalks. Created by Steve Waldeck, it is meant to illustrate sunlight filtering through a forest’s canopy of heavy leaves.

At Philadelphia International Airport, a cunning bird formation (made of over 6,750 cast pewter models of various species, divided into six adjacent suspended installations) mimics first a flying goose, then a vintage DC-3 plane. The configurations are riveting. The artists, Ralph Helmick and Stuart Schechter, installed “Impulse” in 2003. The two had previously banded together for 2001’s “Rara Avis” at Chicago Midway – where what appears at first glance to be a giant red cardinal turns out to be made of 1,800 pewter aircraft figures – and later finished a trilogy with 2005’s “Landing” at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. This piece employs a kindred concept, with birds on wires forming a pointillist snow goose. The goose lands in the rain – intimated by acrylic spheres – with a reflection on the water formed by individual cast metal salmon.

Janet Echelman’s “Every Beating Second,” a 2011 ceiling installation at San Francisco International Airport, harks to two quintessential San Francisco icons: a beat poem by Allen Ginsberg in its title and the Summer of Love in its color choices. Consisting of three pendulous forms made of netting (Echelman’s oeuvre is inspired by watching net makers on a beach in India years ago), the shapes subtly move with air currents in the terminal.

.jpg) Artist Janet Echelman’s sculpture “Every Beating Second,” commissioned for San Francisco International Airport. MUST CREDIT: Studio Echelman

Artist Janet Echelman’s sculpture “Every Beating Second,” commissioned for San Francisco International Airport. MUST CREDIT: Studio Echelman

Echelman, 54, wanted natural sunlight to be one of the piece’s elements, so she cut holes in the roof of the corridor after studying the beam structure. (The Boston artist admits it was “not easy” to convince airport authorities to agree to this.) “I have learned to work with infrastructure,” she says.

That light casts shadows on the terrazzo floor below, but in a nod to what might be, she has manually created much larger, colored shadows, “which would only exist if the entire roof were removed. My piece swoops down from an unseen sky.”

The San Francisco Arts Commission commissioned the work and provided Echelman with a written brief outlining its goals, including a “Zone of Recomposure following security check.” Echelman says dryly that she found that an “intriguing challenge as an artist.”

Much of her other work can be found outdoors in cities around the world, tethered and nonchalant against wind and vagaries of weather, just as nets are supposed to be. So “Every Beating Second” gets a little boost, with “computer-programmed airflow” listed as one of its materials. “It’s important to have art meet us where we spend our lives,” she says. “Art can enrich the quality of every moment, so why wouldn’t we enrich the immense amount of time we spend waiting for flights?”

In turn, she recommends Nick Cave’s “Palimpsest,” a large-scale hanging tapestry made of beadwork at the Tampa International Airport’s rental car center. At 45 by 70 feet and an inch thick, the piece consists of jewelry-size beads (Echelman wonders how much it must weigh). It took workers 10 months to create the work according to Cave’s design.

Anyone still pining for Prince – and who isn’t? – can see a Paisley Park-size mural of him at the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport. The 16-by-24-foot aerosol-on-canvas mural by Rock Martinez, “I Would Die 4 U,” moved to the airport in January from its previous displays in two museums since its 2017 creation. This beautifully trippy painting of the singer with a paisleyesque background is located near the Terminal 1 pop-up shop selling all things Prince-related and will remain until January 2021.

The mural’s genesis is fascinating. Martinez, 39, had been painting a street mural in 2016 in Minneapolis, where he lives half the year (the other half he’s in Tucson). He says: “I had heard Prince was sick and on an ER flight to Chicago. I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool to do a get-well card for him?’ So I went around the corner and started doing a portrait of him.” Someone drove past in a car and shouted, “Hey, write ‘Rest in peace!’ on it.” Martinez’s tribute instantly became a memorial.

Intent on his work, he didn’t realize a crowd had gathered behind him watching. The next day, his painting was on the front page of the Minneapolis Star Tribune, and soon thereafter the Weisman Art Museum in the city commissioned him to create a piece for its show on Prince.

The concept was for Martinez to paint inside as performance art, but “spray paint is volatile, with you breathing it in. You can’t paint in a museum,” he says. For protection, Martinez wears a respirator mask in enclosed spaces, which wouldn’t be available to the museum patrons.

Instead, he worked with the piece’s six 8-by-8-foot canvas panels in a warehouse that didn’t permit all of them to fit on the wall at the same time. “I’d put the top three panels at ground level to paint. It was more or less fingers crossed that everything would line up,” he says. It wasn’t until the piece was installed at the Weisman that he finally saw all six components together.

During the work’s installation at the airport in January, Martinez watched people stop and engage with it – and with him, not knowing he was the artist. “Art brings people together,” he says. “You’re talking to someone who might not otherwise be talking to you – all because of this piece that wasn’t there yesterday.”

Many airports host rotating exhibitions, such as Portland International Airport and Dallas Love Field. With some luck and the resolve to spend your layover in motion, you can take in soul-adjusting pieces at almost any stop you might find yourself.

.jpg)

.jpg)

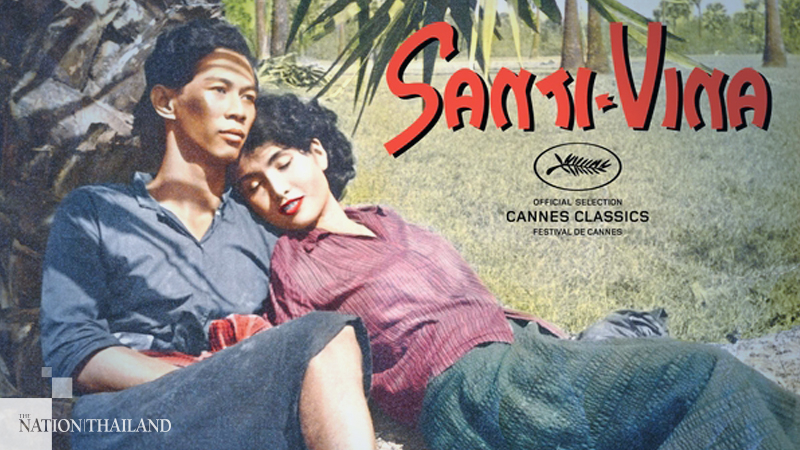

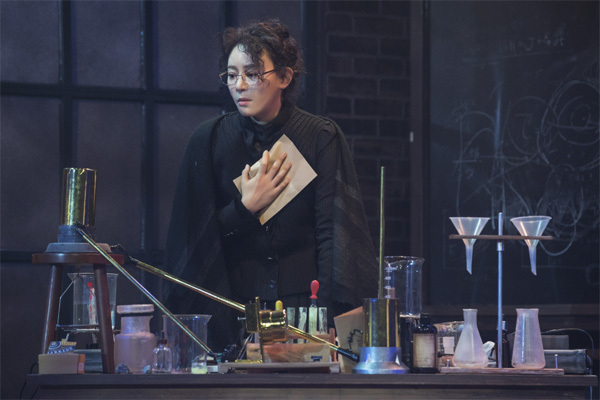

Musical “Marie Curie” (LIVE Corporation)

Musical “Marie Curie” (LIVE Corporation)

“Blue Mustang,” a 32-foot sculpture by Luis Jiménez, at Denver International Airport. MUST CREDIT: Denver International Airport

“Blue Mustang,” a 32-foot sculpture by Luis Jiménez, at Denver International Airport. MUST CREDIT: Denver International Airport.jpg) Artist Janet Echelman’s sculpture “Every Beating Second,” commissioned for San Francisco International Airport. MUST CREDIT: Studio Echelman

Artist Janet Echelman’s sculpture “Every Beating Second,” commissioned for San Francisco International Airport. MUST CREDIT: Studio Echelman