The battle for Notre Dame: As the cathedral rises from the ashes, a tug-of-war is waged over its transformation. PARIS – Earlier this month, the French general tasked with overseeing the restoration of Notre Dame confirmed some terrible news: Even now, nine months after a catastrophic fire in April destroyed the cathedral’s spire, roof and some of its vaults, its fate remains uncertain. “The cathedral is still in a state of peril,” Jean-Louis Georgelin told the French broadcaster CNews.

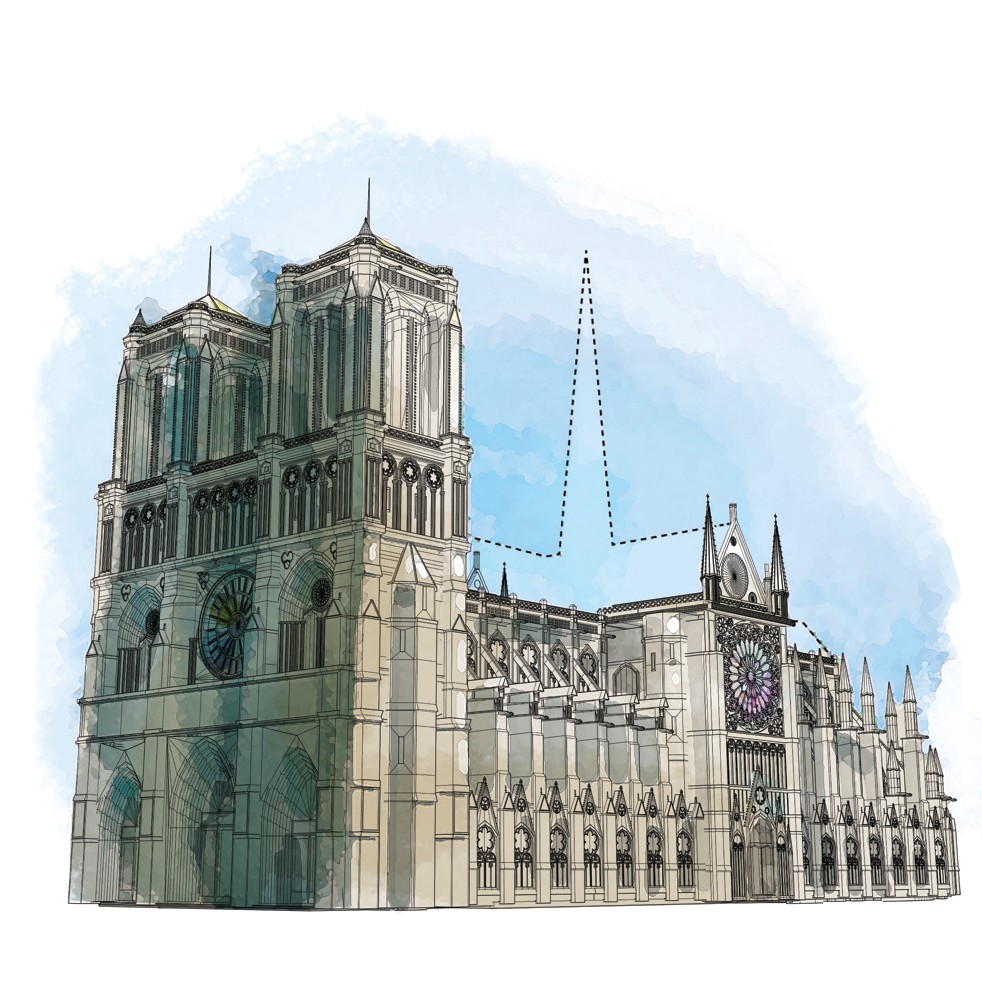

There has been renewed anguish in France. The holidays passed without a Christmas Mass in the beloved national icon or a Christmas tree on the public square outside its richly decorated west facade. When I visited in October, I passed by only once, and it was painful to see the great church off-limits. The writer Hilaire Belloc once described Notre Dame as a matriarch whose authority is familiar, tacit and silent. But she now seems not just reticent, but mute.

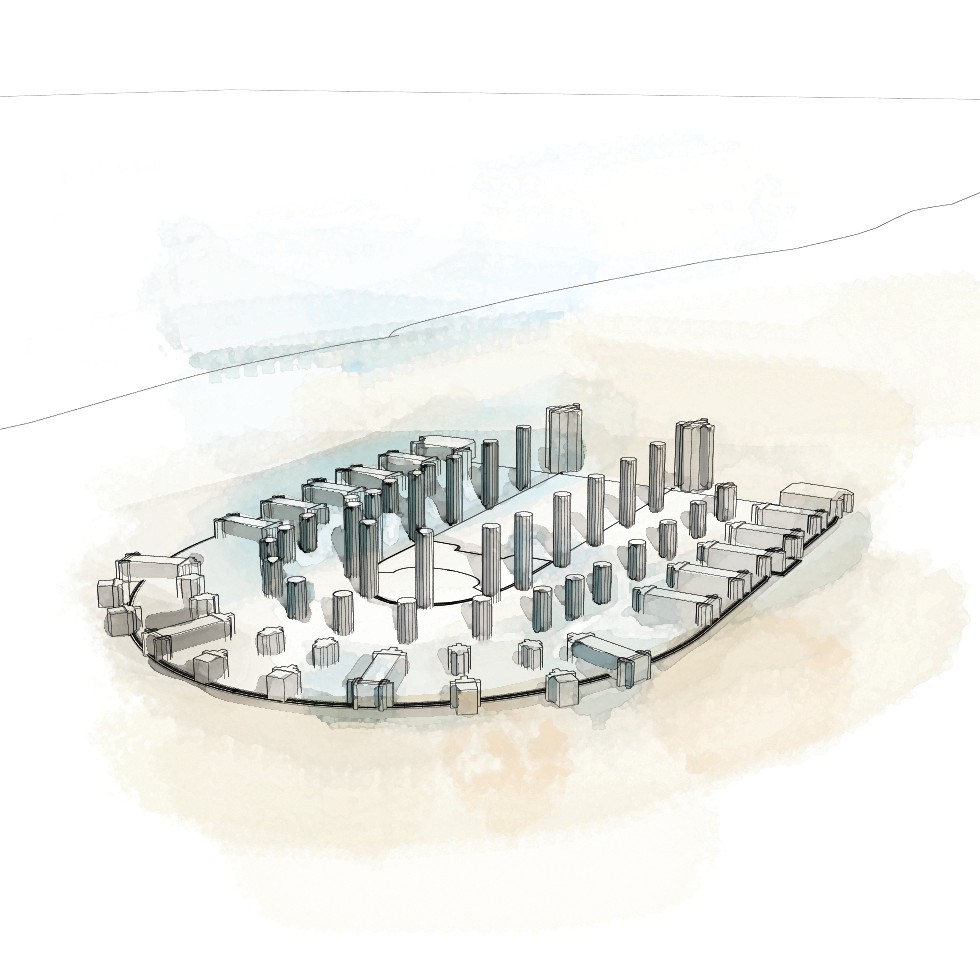

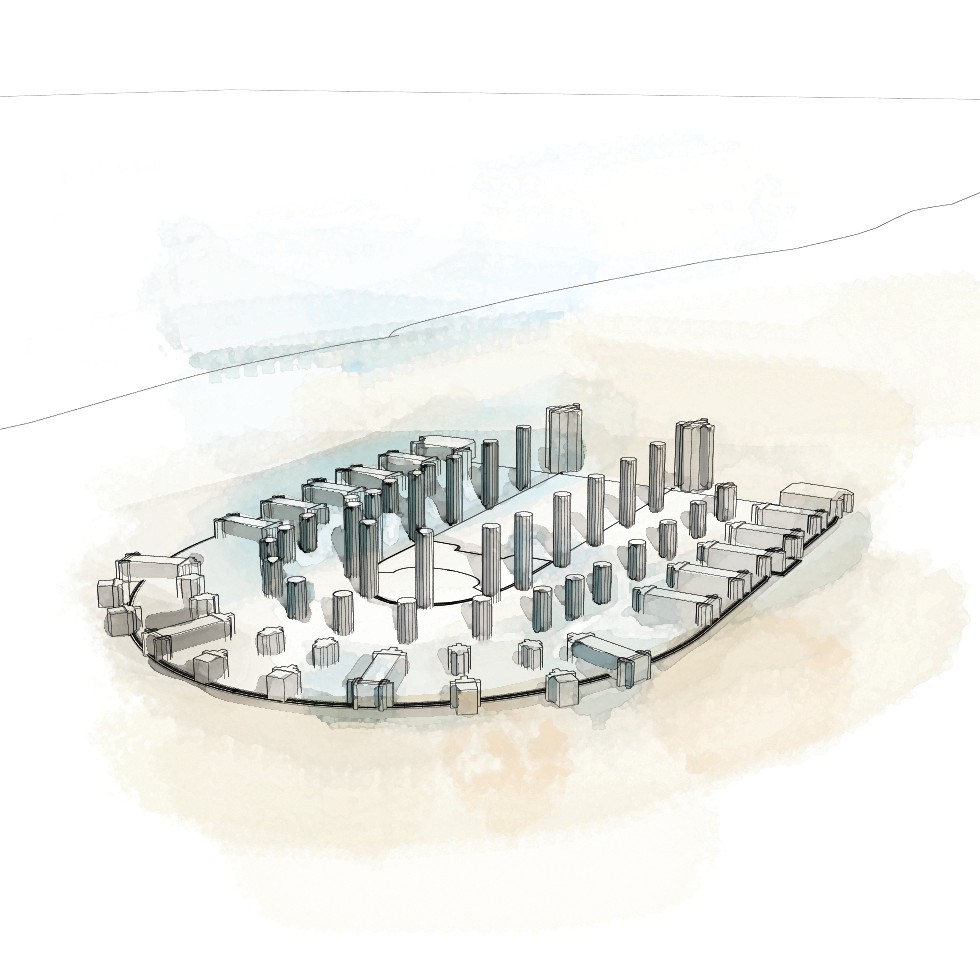

With King Louis VII and Pope Alexander III in attendance, the first major phase of construction began with the laying of the cornerstone in 1163. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post illustration by Aaron Steckelberg

As the public commission headed by Georgelin met for the first time in December, it was clear that the country was still far from any consensus on how the cathedral will be restored. Weeks earlier, Philippe Villeneuve, chief architect of the country’s historic monuments service, said in a broadcast interview that he would resign rather than allow a modern spire – as proposed by French President Emmanuel Macron – to be built atop the cathedral’s roof. In response, Georgelin told the architect to “shut his gob.”

.jpg)

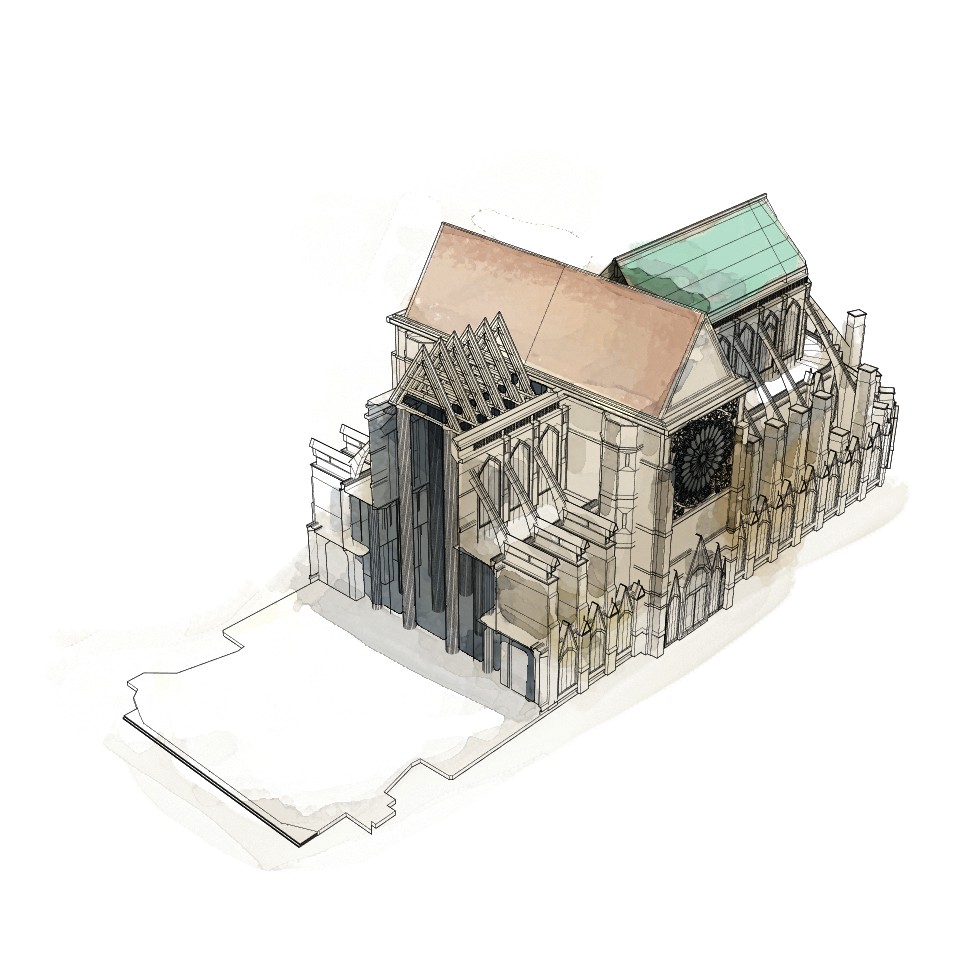

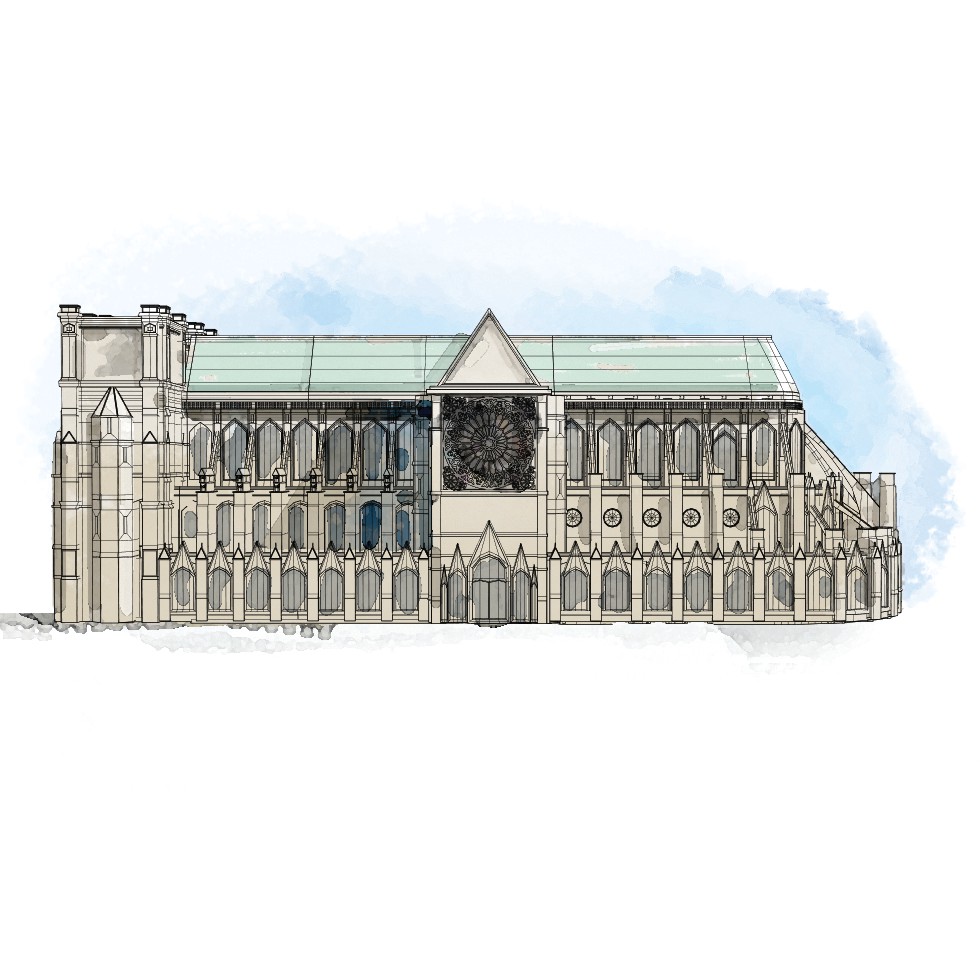

By 1182, much of the cathedral’s choir – the liturgical core of the building, then reserved for the clergy – with its iconic flying buttresses supporting its tall walls and roof, had been completed. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post illustration by Aaron Steckelberg

That comment made international news, although in France it wasn’t out of character for public discussion of architecture and preservation.

Over the next decades, work on the nave pushed the cathedral’s spine to the west. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post illustration by Aaron Steckelberg

“This debate is classic,” Philippe Barbat, director general of heritage at the French Ministry of Culture, said in interview last fall. “Do we restore it as close as possible to what we understand by analyzing the historical context of the building, or do we try to make something more creative?” Barbat cites the glass pyramid at the Louvre, designed by I.M. Pei as a modernist intervention at the heart of one of the city’s sacred cultural spaces, as an example of the latter.

By 1220, the basic form of the early cathedral was essentially finished. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post illustration by Aaron Steckelberg

And change is classic, too. Although there have been centuries during which the architecture of Notre Dame stayed mostly the same, especially after the major construction work was finished in the middle of the 13th century, it has undergone major transformations throughout its history. As France, and much of the rest of the world, contemplates what will become of the grand cathedral, it’s clear that the final result will be an amalgam: of history and fantasy, the 12th century and the 21st, the imaginary building seen in art and described in literature, and a pile of stones that has been made and remade for almost nine centuries.

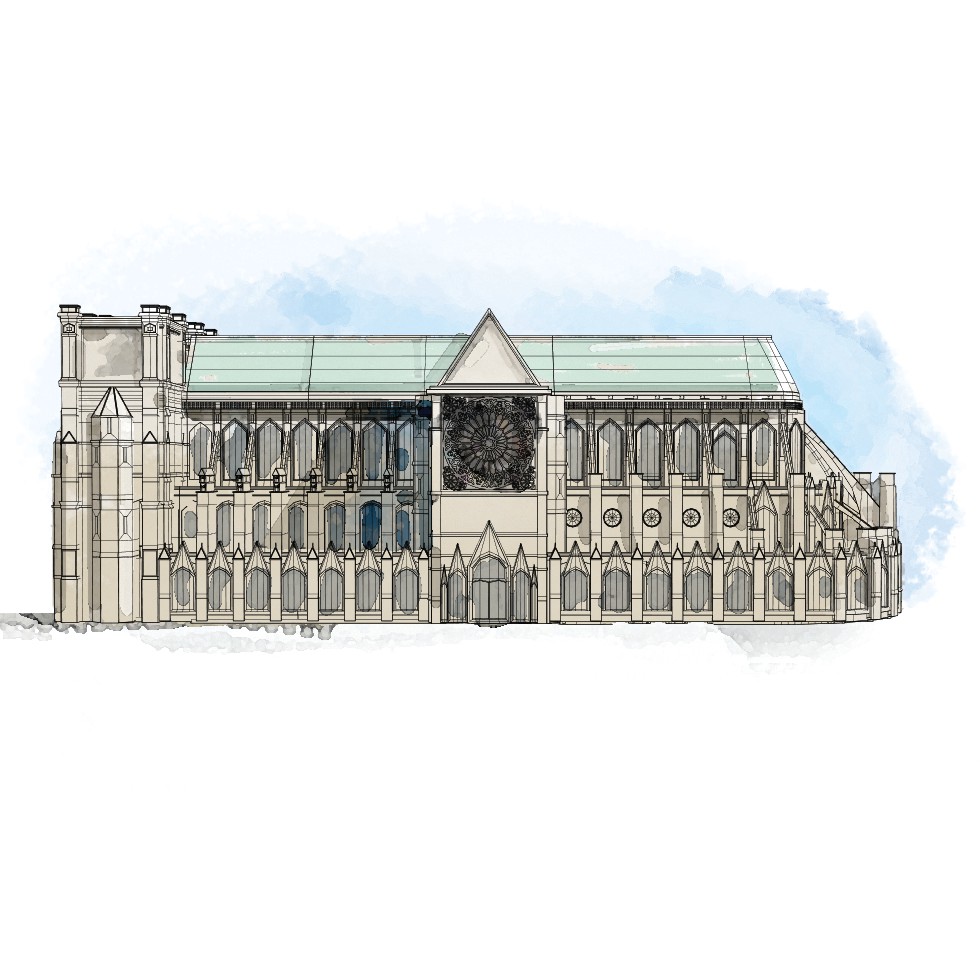

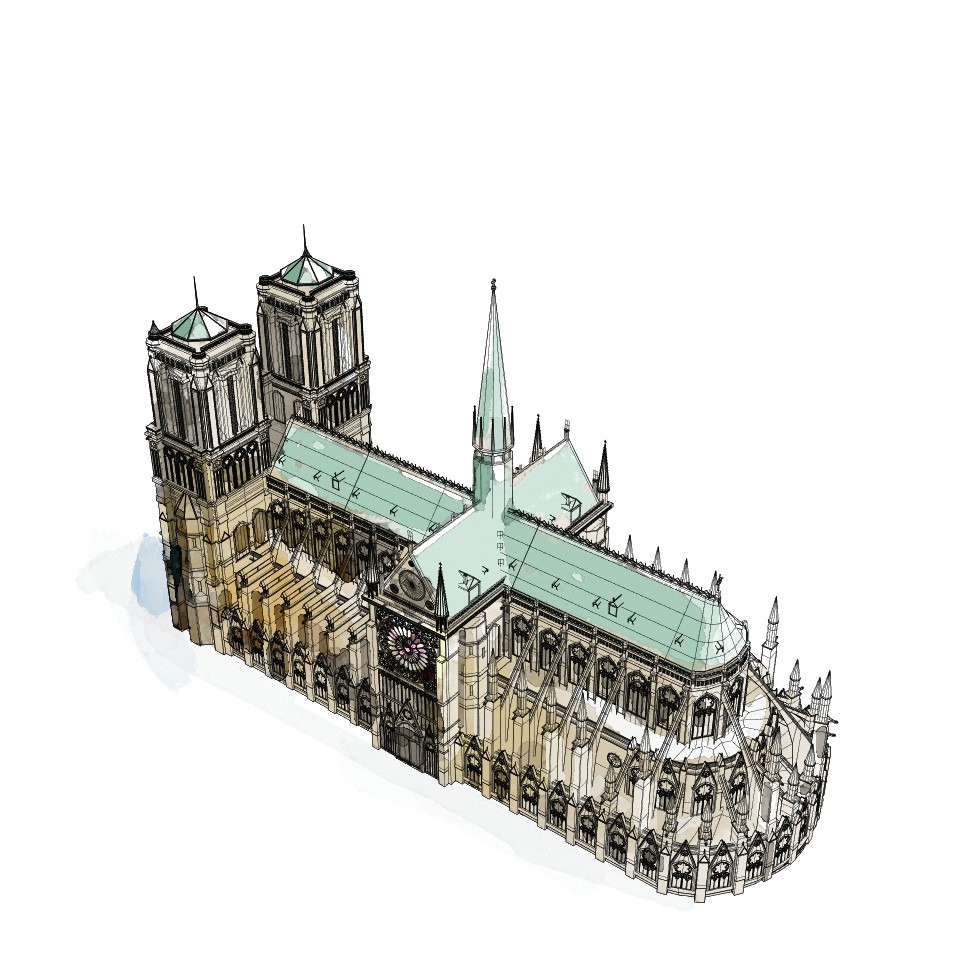

Beginning in the mid-1220s, much of Notre Dame was remade to be more in line with contemporary architectural tastes. The two western towers were finished and a spire was added to the crossing of the nave and transept. The last major phase of the original construction ended in the mid-14th century, more than 150 years after it had begun. By the late 18th century, the original spire was removed before it could collapse from decay. The cathedral remained without a spire until 1859, when one designed by Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc was added as part of an extensive 20-year renovation. Over the next 160 years, alterations and repairs continued to be made. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post illustration by Aaron Steckelberg

As Notre Dame has been rebuilt and repaired over the centuries, there have been many cries of sacrilege. Shortly before the French Revolution, it was whitewashed, leading one prominent critic to grumble that the edifice had “lost its venerable color and its imposing darkness that had commended fervent respect.” And beginning in the 1840s, after decades of little maintenance, sporadic use and sometimes misguided efforts at repair, it was “restored” so thoroughly that many historians came to think of it as a 19th-century church, not a medieval one.

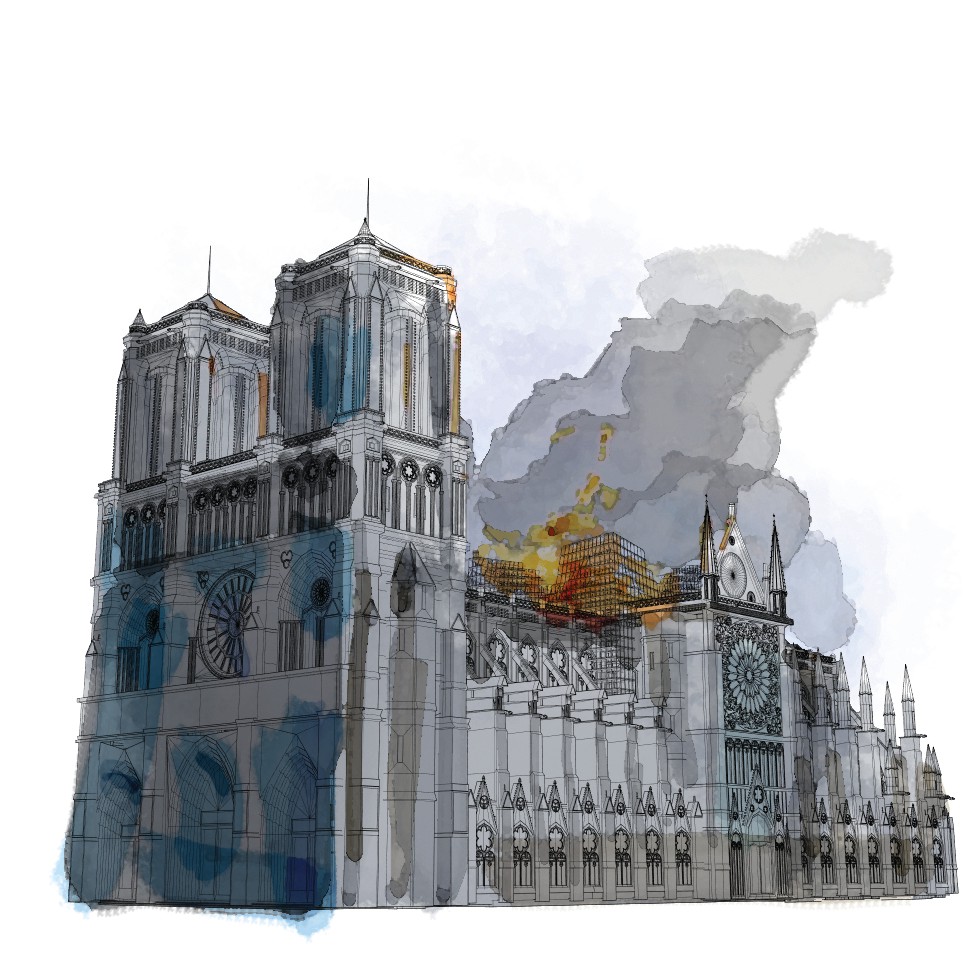

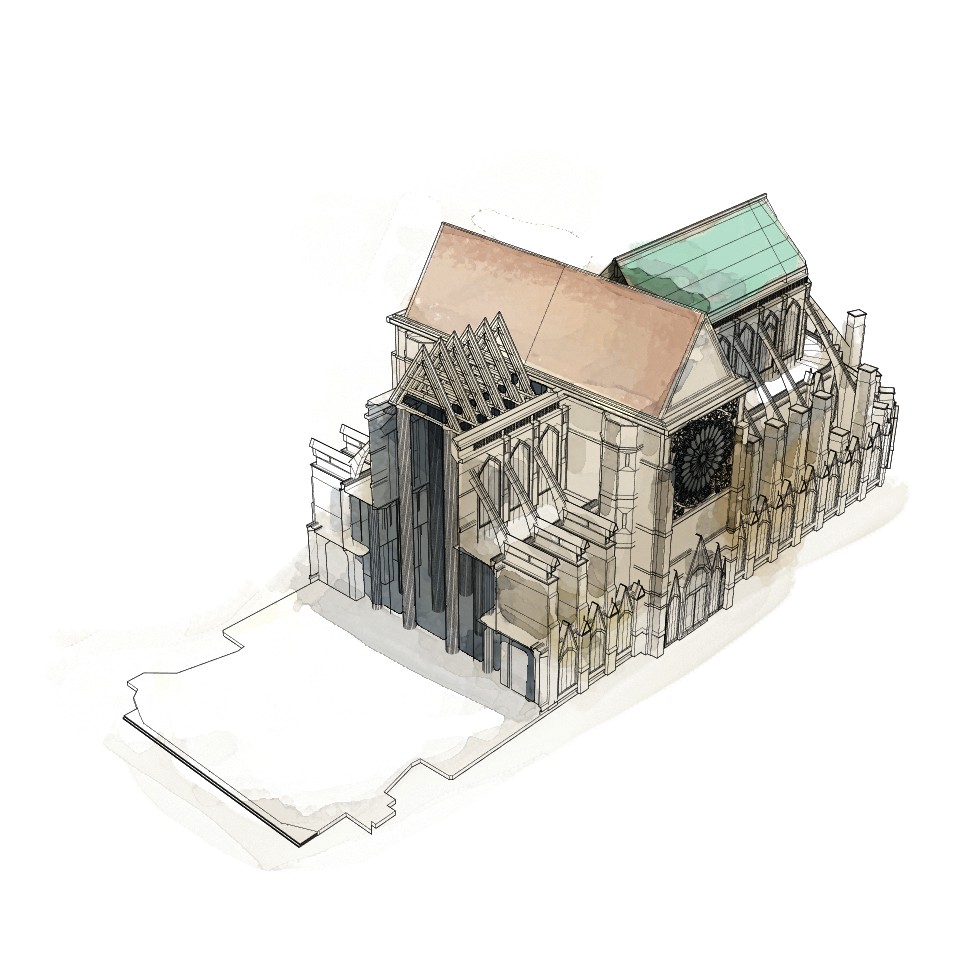

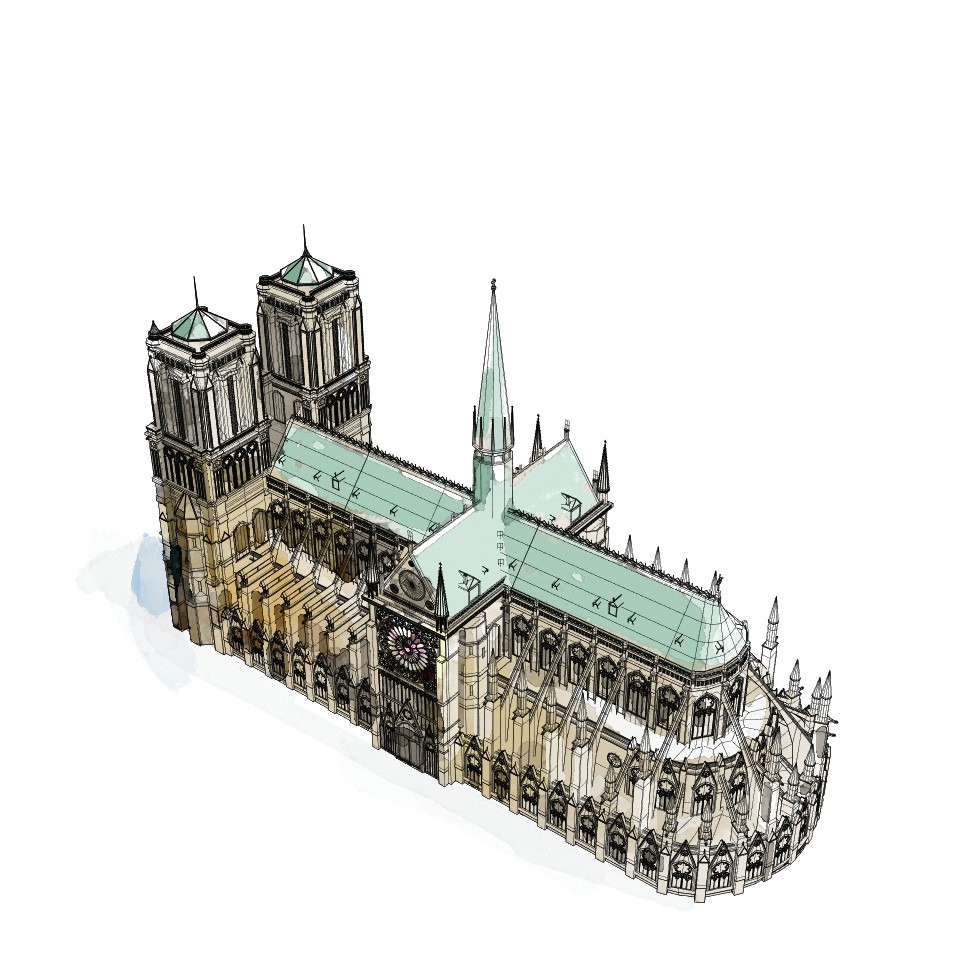

In the spring of 2019, the most recent renovations to the cathedral were underway. Scaffolding was erected around the spire to make repairs, and days before the fire, 16 statues at the base of the spire were removed. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post illustration by Aaron Steckelberg

One of the most significant transformations was probably precipitated by a fire in the 13th century, perhaps similar to the one in 2019, in the roof space above the vaults. Whether the damage forced the cathedral’s stewards to rebuild, or was simply a good pretext to update the building, isn’t clear. But the change was extensive.

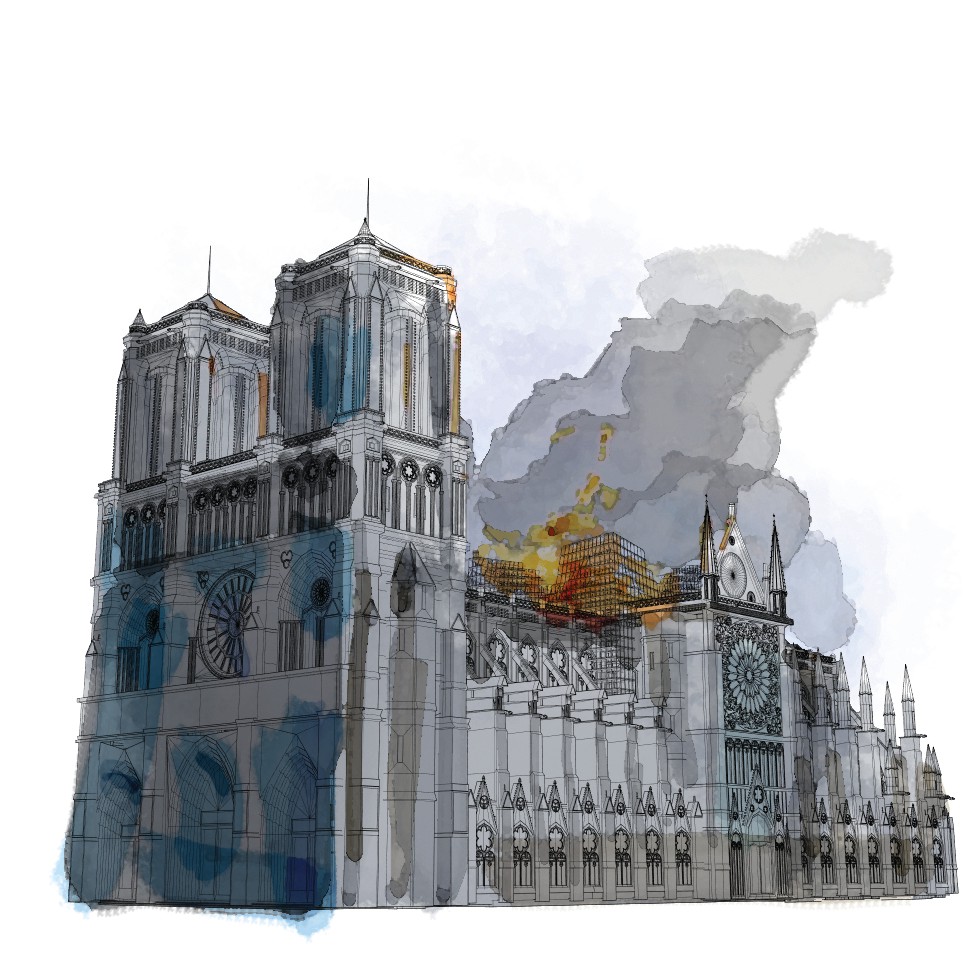

On April 15, a massive fire broke out. Over several hours, flames raged and eventually destroyed Notre Dame’s spire, roof and timbers within. An official cause has still not been determined, although early speculation centered on an electrical source, or a discarded cigarette. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post illustration by Aaron Steckelberg

“Having been around for a mere sixty years, Notre Dame had already been eclipsed,” Dany Sandron of the Sorbonne and the late Andrew Tallon of Vassar write in a forthcoming book about the cathedral, based in part on their comprehensive laser measurement of Notre Dame before the 2019 fire. Elsewhere, in 13th-century France, new cathedrals were being built, and old ones disassembled and reconstructed, to make them taller, lighter and more vertical, and to introduce more light, as if they were made from taut curtains of glass, not heavy columns of stone. And so Notre Dame’s clerestory windows were enlarged, the roofs changed and the flying buttresses reconstructed, although the cathedral remained relatively dark despite its fashionable update.

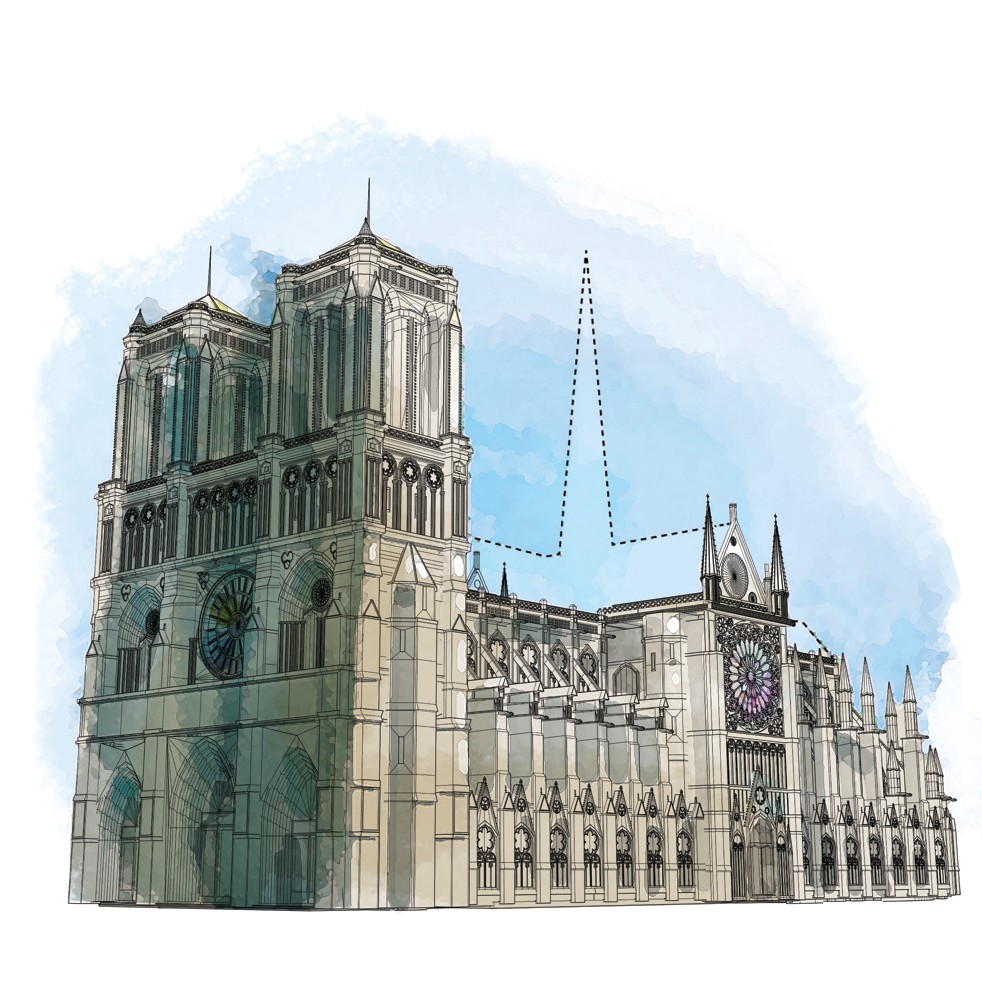

After the fire, debate began almost immediately about the cathedral’s restoration. Should it be returned to its exact pre-fire configuration? Should the 19th-century spire be rebuilt? Or should it be updated for the 21st century and beyond? MUST CREDIT: Washington Post illustration by Aaron Steckelberg

The second radical transformation dates, in part, to 1831, when Victor Hugo published the novel known in English as “The Hunchback of Notre Dame.” The book, set in the 15th century, was a phenomenal success, and the church itself was a major character in its drama of love, lust and betrayal. Hugo intended the novel to ignite interest in France’s legacy of gothic and medieval architecture, and he succeeded. Notre Dame, then in a state of grave disrepair, was rediscovered, and various government committees and commissions were established to help the country address what we now call cultural heritage and historic preservation.

Repairing Notre Dame was one of the most urgent projects, and Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, one of two architects put in charge of restoration, began to undertake extensive and controversial changes. Perhaps no one in the history of the cathedral understood it better – its quirks, structural oddities and weak spots – and no one was more passionately hostile to earlier renovations that had altered its gothic design. But Viollet-le-Duc’s definition of restoration was more like that of a contemporary theater director approaching an old script than a preservationist working with scientific and historical rigor: “To restore a building,” he wrote, “is not to maintain, repair, or redo it, but to reestablish it in a finished state that may never have existed at a given time.”

Viollet-le-Duc changed the windows, added decorative elements to the base of the flying buttresses, remade statues, and created wholesale many of the grotesques, chimeras and gargoyles that visitors often assume are the essence of the cathedral’s gothic character. He also built a new spire, out of wood and lead, to replace the one that had been removed in the mid-18th century because it was no longer sound.

Those changes rapidly became embedded in the public memory of the building. I recall receiving a postcard from Paris that showed a classic image: the Eiffel Tower, with one of Viollet-le-Duc’s gargoyle figures in the foreground. But it didn’t contrast old and new, simply two visions of the 19th-century remake of the city.

One of the most famous images of 19th-century France was an 1853 etching by Charles Meryon called “Le Stryge,” or “The Vampire,” which shows another of Viollet-le-Duc’s grotesque Notre Dame figures, its tongue sticking out contemptuously as it watches over a fantasy of old Paris. It helped to define the curiously Parisian sense that the city’s essence is woven of both beauty and squalor, that it teems with contradictions and harsh contrasts, as in a famous poem by Charles Baudelaire: “Brothels and hospitals, prison, purgatory, hell/Monstrosities flowering like a flower …”

After the fire, the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, a Paris museum that includes Viollet-le-Duc’s invaluable collection of full-scale architectural casts of historic French facades and medieval sculptural elements, displayed models, sculpture and other objects related to Notre Dame. The museum embodies the complicated legacy of Viollet-le-Duc, who was for much of the 20th century considered a fantasist, a Walt Disney-like figure who invented his own version of historic architecture. But he also was a meticulous observer, and the documentation he left behind may be essential to restoring Notre Dame.

“We know we can construct it exactly like it was,” says Francis Rambert, director of the museum’s architectural design department. He is standing in front of Viollet-le-Duc’s model for the wooden spire, a small-scale sculptural marvel in itself. “But the question is, do we need to sacrifice all those trees?”

The spire and the wood have become intertwined flash points that seem to divide French opinion not into clearly opposed ideological camps, but into myriad fragmentary alignments of opinion, as complex as one of the cathedral’s rose windows. There are environmental issues, aesthetic issues, cultural issues, patrimony issues and financial issues.

Is wood necessary? Would lighter materials be better, or do the vaults need the heavy weight of wood to make them secure? Is satisfactory wood available? At one point last year, a Ghanaian company even offered to dredge up giant trees preserved and strengthened by submersion when land was flooded for a dam in Africa in 1965.

The current debates and controversies have uncovered a deeper admiration for Viollet-le-Duc and his architectural changes than might have been apparent a quarter century ago. “Was he some kind of genius or someone who was a megalomaniac?” asks Barbat, the government heritage director, who adds that opinion about Viollet-le-Duc has changed markedly since the 1990s, with growing acknowledgment that his changes have become part of the cathedral’s history. Indeed, when a damaged part of the church’s Porte Rouge was repaired recently, one of Viollet-le-Duc’s elements was meticulously reproduced, a sign that preservation now includes older, 19th-century restoration efforts.

In the end, it will probably be Macron who determines the new form of Notre Dame, although it’s unclear how much he will defer to experts, traditionalist voices, the Catholic Church and the concerns of preservationists. French presidents generally want to put their stamp on Paris, such as Georges Pompidou’s support for a modern cultural center, which eventually became the Centre Pompidou, a bristling postmodern architectural masterpiece, or Francois Mitterand’s championing of I.M. Pei’s Louvre pyramid project. Macron, young, arrogant and determined to chart a new middle course through the fault lines of French political life, has his perfect signature project: the restoration of an ancient building with a modern twist.

“As for the decision itself, I would say that only the president can answer this,” Barbat says. “He was really involved since the night of the fire when he was present at the cathedral. Most likely he will speak about it with the head of the (commission), General Georgelin, but also the minister of culture. Afterward, I cannot answer precisely what he will decide alone in the loneliness of the presidency.”

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)